Black, White, or Other?

“Pedro, Pedro, go back to Mexico.”

“Pedro, Pedro, go back to Mexico.”

“Pedro, Pedro, go back to Mexico.”

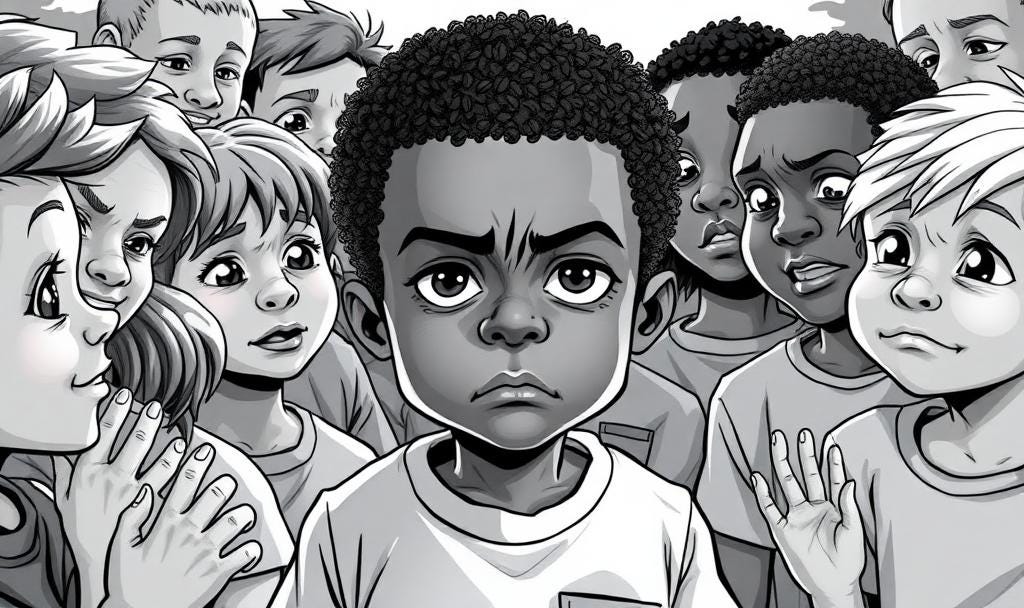

Being Black and growing up in the South—between Virginia and Mississippi—with a name like Pedro Senhorinha Ramos Montero Silva brought in many unwelcomed experiences in my life. One of which was the othering that happened whenever I switched schools, which happened quite a bit due to the economic insecurity that we lived in. And with a name like Pedro in a community where most people categorized themselves as either Black or White, people just didn’t know where I fit in. So, I was often deemed “some kind of Mexican”. Which basically was the catch all for Latino. But in those days Latino wasn’t even an option. In fact, even on the demographic forms back then, the categories they offered were literally only Black, White, or Other. And despite my protests that I only identified as Black, I was consistently deemed other, foreign, or “not like us”.

Despite how it adversely affected me in my early years, I have long understood that categorizing people is a natural function of the human brain, helping us make sense of the world quickly. In certain contexts, such as providing language translation, accommodating dietary restrictions, or ensuring accessibility, categorization serves a practical and even necessary role. But, when we lack an understanding of how bias operates in our minds, such as the way people react to me when they hear my name, categorization can reinforce and exacerbate negative biases, particularly those rooted in our instinctual need to assess safety. This is why I had such a challenge in the South where the Black and White divide was so stark. My name made me unconsciously dangerous to people. In their minds—even though they didn’t know how to articulate it at the time or now—Black people and White people were always trying to assess “whose side?” I was on. In other words, I was suspect. Something that unfortunately, I still deal with today. But, because of a deep understanding of how bias works in our brains, I am far more capable of navigating it than I was then.

In my elementary years, I didn’t initially understand how the culture in America had been designed to put folks into racial, ethnic, gender, and ability based hierarchies to name a few. Because I came from an incredibly diverse family, equality was my “normal”. It wasn’t until I started going to school with a mixed demographic that subscribed to the social strata that I began to put together the order of things, which began with my grandmother telling me on my first day, “Tell White people you are Portuguese so that they will treat you better.” Even though I was only 5, I knew that something wasn’t right about that. So, I told my grandmother that I wouldn’t do that. To which she responded, “I am just trying to keep you safe.” Little did she know how ineffective that strategy was.

At the core of these American hierarchies that made my grandmother think she was serving me, is the construct of Whiteness as the pinnacle of privilege, with colorism functioning as an insidious tool to determine one's presumed proximity to it. The lighter one’s skin, the closer they were perceived to be to Whiteness, which at times could afford one certain privileges—yet these privileges came at the internal cost of forcing folks to navigate the tension between conditional acceptance and the erasure of their authentic identity.

I know for certain that in my own experience, bearing a Latin-sounding name, has often made White people more curious about me than they might be about other Black people. This is because their subconscious biases led them to see me as more palatable or ambiguous rather than immediately placing me in the rigid category of “Black” which for many evokes all kinds of responses. However, this curiosity often came with a social penalty among Black people until they really got to know me. Because of their own biases, some couldn’t help but see me as an accomplice to Whiteness rather than fully belonging to the collective Black experience—even though I lived in their same circumstances or worse, was more well versed in Black history, and believed I had a responsibility to live a life worthy of the deaths of Jesus, Martin, and Malcolm. But old constructs die hard. So, I have lived my entire life contending with them whenever I encounter someone whose amygdala has been hijacked by these homegrown American biases that infect so many of our relational encounters especially among Black and White American folks.

However, it isn’t just Blacks and Whites that are navigating these tensions. As America became increasingly diverse, our issues were reinforced by the fact that foreign-born individuals, regardless of their skin tone, often took advantage of the reality that they “ranked higher” in the social hierarchy than even light-skinned Black Americans because their presence did not immediately stir the deeply ingrained—yet often unacknowledged—guilt and shame that many White Americans carry due to the historical legacies of slavery. My own family took advantage of this and tried to leverage this in many ways that make me cringe to think about. Some of my Black American family unconsciously played into it by reveling in the proximity to “other” they could draw from through their relationship to my Portuguese and Cape Verdean-ness on my dad’s side. And my dad definitely used it to his advantage.

This dynamic shows how the American racial order is not just about color, but about narratives, perceptions, and the ways people are positioned within a system designed to uphold inequity. And this is the context in which my identity was formed. The fact is that without intentional awareness, our biases, which are essentially mental shortcuts, can lead to snap judgments that uphold stereotypes, fuel discrimination, and create divisions rather than fostering deeper understanding. I am such an advocate for people waking up to how they are influenced by these biases because I know very intimately how they prevent far too many of us from fully experiencing our lives and the people we share them with.

Bias By Us

If you have been following my writing, you know that I have a passion for helping people to live more fully into their power. Perhaps it is being a descendant of enslaved Africans or maybe it was having a mom who put me through 18 years of boot camp, but I have a really hard time watching people abdicate their inherent power because they have been trained to fear the Unknown.

Side Note: Actually, it just occurred to me that perhaps one of the reasons that I have made it my mission to help as many people as possible wake up from this pervasive hypnotic fear state is because, in essence, I am the Unknown. When the school system and even my own Black family tried to get me to check that “Other” box as if it was an upgrade from being Black, they exiled me to the Unknown. And when I refused to check that Other box and chose Black, it seemed as if the response to me was, “Oh you want to be Black even though you have that “Get out of Black free” card? Then we are going to make sure you know what it feels like to be Black in America.” And from then on the “Bias Bots” that live rent free in so many people’s brains made it their mission to make me feel the pain of choosing Blackness.

"You only are free when you realize you belong no place - you belong every place - no place at all. The price is high. The reward is great."

Maya Angelou

Below is a video introduction that I made to the Smithsonian Institute’s Traveling Bias Exhibit that—at the time of this writing—is being hosted by the Boulder County Jewish Community Center. I was one of the speakers for the opening of the exhibit and decided to volunteer as a docent for it. Since doing so, I have introduced scores of people to the exhibit. And because of my background in consciously living, studying, and teaching these concepts, I am able to go deeper into the implications of allowing unexamined biases run our lives.

When you first enter the exhibit, there is a definition for bias that sets the tone for the whole space which defines bias as a preference or prejudice either for or against another thing, person, or group. But, because people tend to spend most of their time in protection mode, they have a bias against the word bias. They tend to equate it only with prejudice, which has the connotation of “bad person”, which then freaks most people out because they subconsciously think that “bad people” are not worthy of living. So they unknowingly experience the thought that they might be biased as threat to their own survival, so way too many of us basically mentally check out at the suggestion, thus further entrenching our biases. Exhausting right. And yet most of us live like this every day of our lives without knowing it.

This is why I love this exhibit so much. In many ways, it does participants the service of making the implicit explicit, which if the first step in being able to address it and make positive changes. But, it isn’t just about making changes so that we are more open to others. Understanding our biases and dhow they function also opens us to ourselves—parts of ourselves that have long been buried by unfounded fears that keep us from ourselves. And that’s what I desire for many people, the experience to truly be present with themselves. On many levels, walking people through this exhibit is like walking them through my brain. For decades I have tried to explain to people concepts such as:

Don’t believe everything you think

Don’t always trust your brain

Choose wonder over rightness

But, it hasn’t been until I have been able to walk people through this exhibit and demonstrate why I am a proponent of these concepts that I watched things click for folks in real time. All of a sudden, it makes sense to people why they shouldn’t always listen to their brains that are constantly warning them of impending danger because they are stuck in their amygdala. As Mark Twain famously said, “I've had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.” Does that sound like something you could say as well? If so, you have a lot of company, because everything around us is pumping the fear message incessantly and very few of us know how to turn it off. That is bias by us at work. But, it doesn’t have to be this way. And that is what I am working to share with folks as difficult as it seems to be.

The amygdala is a formidable opponent. Because it is fully formed even before we leave our mother’s wombs, it has an incredible head start on our prefrontal cortex which is responsible for our brain’s executive functions, but takes a quarter century or more to fully develop, if it ever does. As I discuss in the video below, the amygdala is basically hardwired for survival and is constantly looking for threats in everything and everywhere. It just wants to keep our bodies alive, which most people prefer. Unfortunately, the constant barrage of lies that it tells us in an effort to keep us safe is often a disservice for most of us who are actually safer than almost any people in human history. But, we rarely are able to witness this unprecedented level of safety because, the circular logic that amygdala uses says, “If I am alive, I must be doing something right,” even if what it is doing is constantly making up stories that don’t always apply to the situations we are actually in. An overactive amygdala robs us of our present moment opportunities for joy, rest, appreciation, creativity, etc.

Of course, this isn’t to say that there are not moments when the amygdala does it’s job perfectly. The problem is being able to tell when it is serving you and when it isn’t. And that is why it is important to be able to accept that we are all biased. But these biases are not made of stone. They can be changed. They can be intentionally held and then let go of when appropriate. As one of my teachers used to say, “The brain is a wonderful servant, but a terrible master.”

What follows is an exercise that I guided people through at the opening of the Bias Exhibit and then a short contemplation. I created these because when people engage one another in conversations like this, it actually stimulates their hippocampus, which is the brains filing system. By adding an experience of talking about a difficult subject into our brain’s filing system, it helps question the amygdala’s messaging that tells us that having a conversation about a subject like bias is the same as swimming in alligator infested lake in a flank steak bathing suit. I am then offering the contemplation as a way of sealing in the awareness that even in the Unknowns of our lives—which are many—we are afforded the opportunity to face what we cannot control with wonder. I encourage you to try these with others and to sit with not knowing even if for just a few moments.

Connection Activity: The Opposite of Bias Is Wonder (4-5 minutes)

Bias often works silently, shaping how we see the world before we even realize it. But what if the opposite of bias isn’t just “neutrality” or “fairness”? What if the opposite of bias is wonder?

So, let’s explore that together. I’d like you to turn to someone near you—maybe someone you don’t know well—and take turns answering this question:

"What is something you have learned or experienced recently that filled you with a sense of wonder?"

It could be anything—a moment in nature, a conversation, an unexpected discovery that surprised and delighted you. Take two minutes each to share, and as you listen, try to notice how it feels to be in a state of wonder.

[Allow time for pairs to share]

Now, let’s take this a step further. What biases might keep you from experiencing a world full of wonder? What are the assumptions, the habits, the mental shortcuts that might stop you from being surprised, from being curious, from seeing something—or someone—new?

Because here’s the truth: we can never have a wonderful world until we have a world full of wonder.

When we allow ourselves to be filled with wonder—about each other, about the world, about what’s possible—we open the door to deeper understanding. Wonder is what allows us to see beyond bias. It’s what allows us to imagine new ways of being together. And it’s what brings us closer to creating the kind of community we all want to live in.

Quieting the Mind - A Contemplation to Renew Our Minds

Beautiful Unknown,

Words cannot describe You. Images cannot depict You. Arms cannot embrace You. You hold All without hands. You Love All without reason. And You give meaning to our vain imaginings whenever we surrender to the Way of Love that casts out fear.

With or without religion, in form and formless, in our sleeping and in our waking, your boundless Wisdom keeps hidden and reveals everything necessary to facilitate the flourishing of all Life. And yet, because of groundless fears, we have too often chosen another Way—an illusion that puts a veneer of reality on what cannot be and leads us to ignore what every conscious being knows. Oneness is Reality.

Mindful of this, we thank you that everything done in ignorance of this reality has failed before it ever began, that all we need do is get still and restoration is assured, and that it only takes a flicker of light to dispel the darkness. May we take every opportunity to meditate on these things until lies are replaced with Truth, forgetfulness is replaced with remembrance, and All things are Known as they were meant to be Known—free from bias and distortion.

May it be so. And so it is.

Resources:

“The opposite of bias is wonder.” These are words to make me become more consious of my internal biases and hardened ideas that could be softened by compassion and a new perspective. Thanks, Pedro.