When I first wrote a movie review for G20, the action film starring Viola Davis, some weeks ago, I did not anticipate that I would write another movie review this soon. But, after watching the film Sinners, starring Michael B. Jordan and directed by Ryan Coogler, I knew I was going to have to share my point of view. Truth be told, I am not one for watching horror flicks. I stopped that decades ago. So, even though I have the utmost respect for the star and filmmaker, I was not planning to see this film. But, when I started hearing about the double standard of magazines like Variety who tried to minimize the success of the opening of this Black led film, I knew I was going to have to get over that moratorium on horror flicks.

"Sinners" has amassed $61 million in its global debut. It's a great result for an original, R-rated horror film, yet the Warner Bros. release has a $90 million price tag before global marketing expenses, so profitability remains a ways away. - Variety

Contrast this message with what Variety had to say about the opening of the Quentin Tarantino film, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, that had virtually the same $90 million budget, but brought in less revenue during opening weekend.

Box Office: ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ Starts Strong With $41 Million - Variety

There’s a lot I could say about why people’s brains function this way. But for the sake of brevity (if that is possible for me), check out my piece, Bias, By Us or check out my interview with

on his show, Egberto Off the Record, where I go deeper into why so many people tend to see what serves their psychological need for safety rather than the reality that is right in front of their faces. Now, on to the review.WARNING: IDEOLOGICAL SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

I’m going to do my best to avoid getting into too many details of the movie. But, if you haven’t seen the film and just planned on looking at it as simply a horror flick, I am about to mess that up for you.

As the title of my review suggests, my opinion of the film is that it is a social commentary and artistic expression on the impacts of colonization on people all over the globe, with a particular focus on Christiantity as a colonization delivery system. Before the film came to its conclusion, there were elements that led me to believe this was the story’s central message. But, this opinion was solidified at the end when one of the protagonists, Sammie, played by Miles Caton, was trying to pray the vampire away using the “Lord’s Prayer” as a defense. Rather than have an adverse effect on him, the lead vampire Remmick, completed the prayer and indicated that “Long ago the men who stole my father’s land forced those words upon us. But the words still bring me comfort.” Remmick the central antagonist, played by Jack O’Connell, was Irish. And with those words, my theory was wrapped with a bow. Let’s see what you think.

A Who’s Who of the Colonized

If there was an award for most diverse cast in a horror film, Sinners would win hands down. It was filled with a Who’s Who of American Colonization All-Stars. Almost everyone was represented from the Indigenous Choctaw who were hunting Remmick in the beginning of the film to Chinese allies of Michael B. Jordan’s characters, Smoke and Stack, twin gangsters who after “traveling the world” made their way back to Mississippi because they would rather “face the Devil they knew.” Heck, even though their were no overtly Latino members of the cast, in the small Mississippi delta town they lived in, there was a tamale shop called King’s Tamales, which suggested that they were even trying to cover Latino (Mexican) representation. Basically almost everyone who has had the lifeblood of their people sucked out of them by the vampiric nature of American colonization was represented in this film, even the poor ignorant people who, believing that their “Whiteness” gives them adjacency to the illusion of supremacy. But, as the film demonstrates, colonization sucks and turns everyone bitten by it into a monster.

Once Bitten

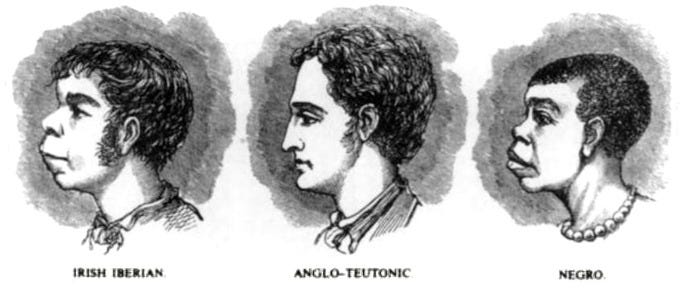

Back when I was still working in the intelligence community, we had a cross cultural communications training where the facilitator said something strange that I would not be able to confirm until I moved to Boston some years later. She said, “Prior to the 1930s, the closest cultural comparison to a Black American woman was an Irish American woman.” I don’t think people would get away with saying that now. But, the point she was trying to make was that because of certain social factors, Irish women and Black women had to play similar roles in their families unlike other White women, Latinas, Asians, etc. And it was in this training that I first saw the picture above.

This illustration from the H. Strickland Constable’s Ireland from One or Two Neglected Points of View which tried to suggest using racial pseudo-science that the “Irish Iberian” and “Negro” had more in common with each other than the “Anglo-Teutonic.” The caption that was featured with this image read:

“The Iberians are believed to have been originally an African race, who thousands of years ago spread themselves through Spain over Western Europe. Their remains are found in the barrows, or burying places, in sundry parts of these countries. The skulls are of low prognathous type. They came to Ireland and mixed with the natives of the South and West, who themselves are supposed to have been of low type and descendants of savages of the Stone Age, who, in consequence of isolation from the rest of the world, had never been out-competed in the healthy struggle of life, and thus made way, according to the laws of nature, for superior races.”

This was of particular interest to me when watching Sinners because the casting choice of the Irish antagonist suggested to me that Ryan Coogler was well aware of these sociological false premises that were made in that time frame. By casting Remmick as Irish, the filmmakers deliver a nuanced blow: when the colonized internalize the structures of power and trade liberation for Whiteness, they become exactly what once devoured them. The undead. Detached from soul, culture, and spirit. Accepting the false promises of immortality through access to unlimited consumerism, the once living being becomes an affect of the system.

In this way, the metaphor of vampirism in Sinners doesn’t just serve as a creative horror twist—it’s a devastatingly accurate stand-in for the extractive, soul-eroding legacy of colonization. Vampires don’t just kill; they drain, consume, assimilate. They leave behind bodies that walk and speak but serve only the pervasive hunger (consumerism) this is never satisfied. That’s why in the world of this film, it’s no coincidence that Remmick, the central vampire, is Irish. It was easy for those with the colonizing spirit to lure them into believing that they could work their way up to becoming one of the consuming immortals simply by assisting and in the assimilation and further subjugation of those who would be seen as their lessers.

Even though many people challenge this as myth, there is a narrative that suggests that, historically speaking, the Irish were not considered White when they first came to America—at least, not in the way Whiteness functions as an exclusive club of power and supremacy in the Western world. They were once the colonized, reduced to stereotypes, demonized by the British Empire, and treated as barely human. This is precisely why H. Strickland Constable compared them to Black people, claiming racial inferiority in a pseudo-scientific framework meant to justify colonial domination. The Irish were othered—until they weren’t. (See this article on how the stereotype of Irish criminality shifted being cops)

The horror of Remmick isn’t just that he’s a vampire—it’s that he remembers his people being colonized and yet has chosen to perpetuate the very same violence onto others. His line, “The men who stole my father’s land forced those words upon us,” isn’t just about Christianity—it’s about memory. And his choice to complete the Lord’s Prayer doesn’t mark him as pious, but as complicit. This literary device is critical to understanding that if one internalizes the tools of their colonizer they essentially become an extension of them. His infection of the poor White townspeople, especially those cloaked in Klan robes, further reveals the deep irony that the virus of colonization infects even those it promises to elevate. Their Whiteness doesn't protect them—it damns them faster. As is seen later in the film when the first of the protagonists is infected.

And that’s part of the brilliance of Sinners. In this small Mississippi town, everyone’s got bite marks—Black sharecroppers, confused White supremacists, white passing Black folks, Chinese immigrants, even global wanderers returning home. That is, everyone except the Choctaw. The only seemingly immune people in the film are the Indigenous characters, whose ancestral memory—and perhaps their ancestral grace—make them resistant to the vampire’s curse. And again, this shows that Coogler was deeply informed by history when making this film.

A Bond Forged In Hunger

I imagine that many people who watched the film are unaware of the relationship between the Irish and the Choctaw specifically. But, during their Great Famine in the 1840s, despite facing hardship themselves, the Choctaw were among the first to send aid to the Irish. And since then, the two peoples have always maintained a bond. Knowing this, I couldn’t help but wonder if Coogler wasn’t trying to communicate that the Choctaw, as representatives of indigeneity, were able to see what those who were bitten by the illusion of colonization were not. All of us who have been assimilated into the colonized mindset, have lost the old ways. This stood out to me as a possible point the film was trying to make through the representation of the Choctaw, who perhaps were trying to save Remmick’s soul, and later through Wunmi Mosaku’s Annie character who used the African old ways to protect her love interest, Smoke. With the way these characters stood out, I could easily see how the film could also be a nod to remembering the indigeneity that Remmick, and by extension almost all Americans, have lost sight of.

If I were to say this movie had particular warnings, they would be: when we trade memory for proximity to power, we rot from the inside out. When we buy into the myths of supremacy, even as survivors of it, we perpetuate the cycle. When we define success as becoming the one who extracts, controls, and consumes, we become vampires—defiling the spirits of our ancestors, haunting our descendants, devouring our communities, and condemning the world to an endless night where vampires reign.

That’s why I titled this semi-review Colonization Sucks. It is because it does. And not just figuratively. It drains the lifeblood from people, cultures, and land. And if we aren’t intentional, if we don’t stay rooted in reciprocal humanity, we risk waking up centuries from now as descendants of Remmick—justifying our hunger while claiming to still find comfort in the words that once enslaved us. And that goes as much for our religious texts as for the founding documents of this still forming country.

Construction. Deconstruction. Reconstruction.

Admittedly, my own critical examination of my personal history with Christianity has very likely biased or at least deeply informed this analysis. But, despite this, I do strive to be as clear-eyed as possible. And it’s from this commitment to clarity that I am asserting that Coogler isn’t just telling a horror story—he’s crafting a layered reflection on power, memory, and spiritual amnesia that is part and parcel of the colonized mind. Whether I’m right about the film’s depth is up for debate. But from where I stand, Sinners is a direct commentary on Christianity as a tool of colonization.

If you’ve read my essay Grieving My Religion Part 1, you know I’m navigating the tension between reverence for the teachings of Yehoshua and disillusionment with how they’ve been distorted by empire. And I’m not alone by a long shot. Many are reckoning with the deep hypocrisy of American Christianity—where the same mouths that recite the words of Christ also spew hate, burn crosses, and bow to systems of domination.

I’m relatively new to TikTok. But, there are people making careers of stating the obvious about Christians. And a lot of them are Black. Believe me, I never thought I would say this. But, every time I see a Black person criticizing Christianity, I get so happy for them. I just can’t help it. Even though I am still personally committed to the teachings of Yehoshua for my life, it was not without doing an extremely critical examination of the religion to include taking an honest no holds barred inventory on it flaws and failings to include it blatantly being used as a tool for White supremacy despite the fact that it emerged out of Middle Eastern and African cultures. So the way I see it, unless someone is able to critique their own beliefs wholeheartedly, I am going to doubt the depth of their convictions. And let’s just say, if Coogler is Christian-ish at all, he absolutely did not hold back on the critiques.

Coogler doesn’t just critique the obvious culprits—White nationalist evangelicals cloaked in violence—he also shines a light on the pious Black Christians in the story. Growing up in that world, I can say from experience: for many, faith can be reduced to a psychological defense against White supremacy. Some embraced Christianity as a bond to their oppressors. Others tried to be “super-Christians”—so devout, so righteous—that their very lives became a quiet rebuke of the hypocrisy that enslaved them. In many ways, it was a strategy: If I can’t escape it, maybe I can be so good that even my enemy feels convicted. It wouldn’t necessarily save your life—but maybe it would stir the consciences of those who indiscriminately and unceasingly violate the professions of their faith. But as hundreds of years of history and this film shows, vampires don’t have consciences. And people are starting to wake up.

Of course, I am saying this as a former “super-Christian. When I gave my life to Christ at six years old, I was all in. I prayed, read scripture, and even bumped Gospel Gangstaz rather than mainstream rap. I was a gospel soldier. It felt like who I was. Who my people were. In fact, I was raised in a church with an “age of accountability”. That meant that, in their minds, I was not accountable for my sin until I was 12. In fact, when I begged to get baptized early, some deacons tried to talk me out of giving up my 6 years of free sinning. But, I was so serious that I didn’t want to wait. Besides, all the really fun sinning was usually reserved for people older than 12. So, I figured why delay the inevitable.

Needless to say, it has been quite a journey for me to get to where I am now. While watching Sinners, I wasn’t just seeing a film—I was seeing an artistic indictment of the world I was raised in. And you know what? That indictment is necessary. When I aligned myself with Yehoshua, I was aligning with spiritual liberation. I was an innocent child that saw reflected in the stories of Yehoshua, a mirror of the systems that were trying to deny my people’s humanity and a Way that one man among an infinitude of awakening souls taught to stand up to it; not whatever this miscarriage of Christ is that is infecting the world that we keep calling Christianity. What I see in this film—even if I am projecting onto it—is a declaration that says, when a tool of liberation becomes a weapon of oppression, something sacred becomes something virulent. That’s the real horror.

Look, even though I want to keep going, I don’t want to spoil the ending. So, I’ll leave you with this: in many ways, this movie is a mirror if for your soul. So, I hope that when you see it, something alive is reflected back. Ask yourself if the real you has a home in this world. And if it doesn’t, are you willing to resist the forces trying to consume you with everything you have? As I’ve shared, there was a season when I couldn’t see myself in the mirror anymore—after a painful rupture with the White supremacist undercurrent in a Black church I loved. I lost myself trying to hold on to what I considered the fulcrum of my identity. And as a consequence, I became, in many ways, a temporary vampire—consumed by the very thing I thought I was fighting. And when I found myself again, I made a promise: Never again.

There’s a line in scripture that says, “What does it profit a person to gain the whole world and lose their soul?” That’s the question Sinners forces us to ask. Not in the religious sense, but as it pertains to consciousness. There is no profit in assimilating into death. The colonial mindset is death—and serving it makes you a servant of death.

Many of us have been seduced into thinking dealing in death will keep us safe from its ravages: economic death, spiritual death, relational death. But that’s a lie. And yes, I know that sounds very Christian. In many ways, it is. Just because I grieve what Christianity has become, it doesn’t mean I’ve abandoned the life at its heart. If anything, this journey has helped me see how expansive that life really is—beyond doctrines, beyond buildings, beyond colonized religion.

For me, Christianity was never supposed to be about control. It was about paying attention to the world as it is and to what makes you come alive. And that’s a universal invitation. The teachings of Yehoshua were never meant to be filtered through capitalism, consumerism, or colonization. They were meant to wake us up.

Howard Thurman put it best when he said,

“Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

Thurman saw through the evil veil of colonization and found the living heart of Christ. He doesn’t have to be an exception. We can all come alive—with or without religion. But it has to start with admitting that a tree truly is know by its fruit. And the fruit of colonization does not nourish, it annihilates. What makes one a “Sinner” is not whether they follow the rules of some religion or not. What makes one a “Sinner” is the denial of the Universe’s all inclusive reality. The word sin itself is nothing more than an archery term that means to miss the mark. And that is what this film is, a cautionary tale on what is the inevitable consequence of choosing complicity in your own oppression as a path to liberation. It just isn’t going to happen because colonization gives nothing. It only sucks the life out of everything.

Now, I would remiss if I didn’t say that in naming the colonized mindset as the vampiric virus that it is, that I am not isolating this mindset to White people. Even though that could be easy to do, the fact is that knowing who patient zero is does nothing to eliminate a disease. So, let me make it clear that that is not what I am trying to do. And I don’t necessarily think that is what the movie was trying to do. After all, there was this underlying theme that once everyone was infected, it would bring about the peace, harmony, and freedom that everyone was looking for. Once the Klan members and the Black sharecroppers were all vampires, they were suddenly on the same team and of one mind. That’s the promise and the compromise of assimilation—the false choices between “freedom through uniformity” or “ascension through assimilation.” Deals with the Devil that I, personally want no part of. But, in my experience, this deal is not simply one that White people take.

As we’re seeing even more clearly in the world and as the film demonstrates, vampires come in all types. I have met more than my fair share of people with White supremacists colonized mindsets who are about as White as Wesley Snipes when it comes to genetics. So, at this point, the folks who value liberation are better off focusing on mental content over melanin content in many spaces. That being said, like the Irish lead antagonist in the film demonstrates, it is easier for some people to be lured into the trap simply because they have been told that it is in their favor. So, if you happen to be White and are reading this and value liberation of all people, stay extra vigilant. Know that these vampires are coming for your neck first. And everyone else, who knows that this system never wanted you in the first place, its time to reconsider where you’re investing your blood, sweat, and tears. Because if you have cast your lots with the colonized mindset, it will always suck for you.

Below the Payline: A Beginning to Decolonizing the Mind

If you’ve made it this far, you might be wondering: What now? Below are some thoughts and cautions for those ready to begin the journey of decolonizing your mind. This is not just for Black folks or other obviously colonized people. The fact is that unless we want liberation for all of humanity, we are operating from a colonized mindset. And to undo it, is the work of a lifetime.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pedro Senhorinha Silva - Live Your IDEALS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.